Chapter 4

Rating Cards.

Transferring Cards

Tracking Rating Players

As someone who has had game protection on my mind since I was a break-in dealer, I was always a little skeptical about the need to know how much a player had won or lost. If his losing bets were picked up and his winning bets were paid the correct amount, then the game was run on the square and who cares how much he won? I thought that anything that took a supervisor’s attention from a game, even for a second, was something that was unnecessary.

But even before I came to wear a suit I realized that a boxman or floorman is paid to be aware of what is happening on his games. If the cage calls the pit and says a player is cashing-out four thousand black, shouldn’t someone be able to confirm that it came from their game? If for no other reason, could the black checks be counterfeit or stolen? Of course we have all worked at or heard of casinos that sweat the money but even before cash transaction reporting became the law, there were numerous legitimate reasons for competent supervisors to know how much money had left their games, which players got it and how they got it.

Using rating cards to track players.

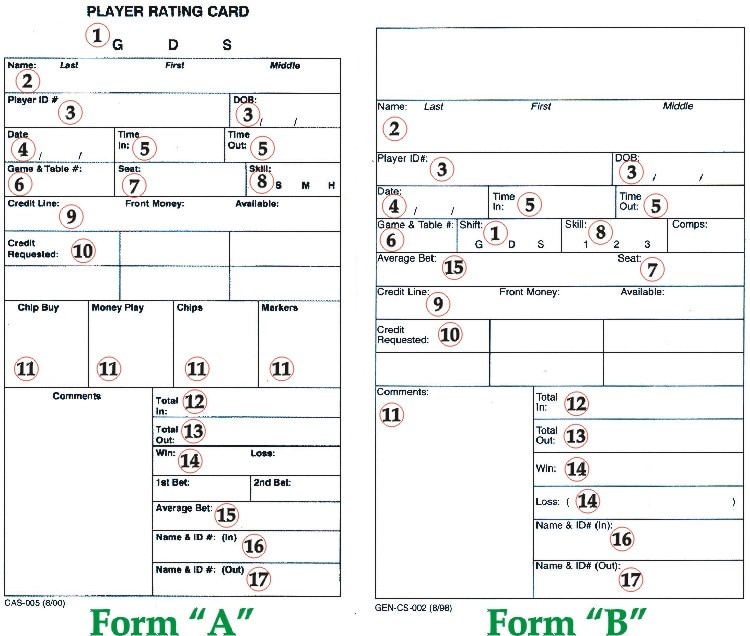

A rating card is a tool to tell management facts that they need to know. A rating card may look complicated to the new supervisor that has never seen one before or even an experienced one that is getting accustomed to a new job and a new form but all rating cards contain the same basic information.

But even before I came to wear a suit I realized that a boxman or floorman is paid to be aware of what is happening on his games. If the cage calls the pit and says a player is cashing-out four thousand black, shouldn’t someone be able to confirm that it came from their game? If for no other reason, could the black checks be counterfeit or stolen? Of course we have all worked at or heard of casinos that sweat the money but even before cash transaction reporting became the law, there were numerous legitimate reasons for competent supervisors to know how much money had left their games, which players got it and how they got it.

Using rating cards to track players.

A rating card is a tool to tell management facts that they need to know. A rating card may look complicated to the new supervisor that has never seen one before or even an experienced one that is getting accustomed to a new job and a new form but all rating cards contain the same basic information.

1.) SHIFT: this is very important to the pit clerk or pit boss that has to sort the cards. Remember, even if it is 1:00 am, if the shift hasn’t rolled, it is still swing shift.

2.) NAME: it has to be legible and spelled correctly. If the player doesn’t want to give his name, then use "R/N" (refused name) and a very brief description so your team can tell this player from the dozens of other R/N’s. Good examples are "black hat" or "gray polo."

3.) PLAYER ID# or DOB (date of birth): it easier to look up a player in the computer using their account number. DOB can be useful if the player has a common name and you don’t know his account number. It is also useful if the player has a credit line and you don’t know his credit line account number yet.

4.) DATE: remember, if it is 1:00 am but the shift hasn’t rolled, it will be yesterday’s date.

5.) TIME IN / TIME OUT: pretty cut and dry here. Time can be written using the conventional method (without am or pm) or using military time. You want to avoid using a time-out time that is later than the time-in time that another floorperson has started this player’s next card, as this will cause overlapping play times.

6.) GAME & TABLE #: BJ 9, CR 4, RO 2 etc.

7.) SEAT: this is very important and easy to write in what playing spot a player is using on a BJ game or what position he is on a crap game. If this space isn’t offered on the rating card, I will write it in the upper right-hand corner of the card.

8.) SKILL: I have never worked in a place that uses this spot but some places use a player’s skill (or lack thereof) in determining their rating. A player that uses good basic strategy in BJ or only bets the pass line with full odds, will get a lower rating than someone who splits fives or only bets the hardways.

9.) CREDIT LINE: this is the total amount of this player’s credit line before he took any markers. Notice the form differentiates between credit extended to a player and front money the player has deposited in the cage. The reason being, a shift boss won’t be likely to raise the credit limit of someone that can only get markers because he deposited money at the cage.

10.) CREDIT REQUESTED: this is where you write in the markers this player has taken.

11.) BUY-INS: form "A" is much better designed to accommodate the necessity of indicating a chip purchase and a "losing money plays" separately. This is necessary for CTR reporting requirements. You will enter amounts using the "|’s" "V's" and "X’s" just like on your sweet sheet or table card.

12.) TOTAL IN: this will be the total amount of buy-ins, unpaid markers and lost checks. Numbers entered in total in, total out and win/lose will be written out in the conventional method, with two thousand being 2000, not 2.0

13.) TOTAL OUT: this will be the amount of the checks the player left with.

14.) WIN / LOSE: how much the player won or how much the player lost.

15.) AVERAGE BET: the average amount of money that player had in action at any one time.

16.) NAME & ID# (In): the floorperson that started the rating card.

17.) NAME & ID# (Out): the floorperson that closed out the rating card.

Cash buy-ins and checks out.

This is the simplest play to track. If a player has bought in $2000 and leaves with $800, then his total in is $2000 and his total out is $800. This will be the case even if his cash-in was a combination of buy-ins and money plays.

How do we know that he left with $800? The answer is almost always the sweat sheet; in fact it is always the sweat sheet if this was the only player on the game. If you had 4.0 black and 2.2 green when this player landed and had 3.4 black and 2.0 green when the player left, then we know you are missing $800 in checks. This is why it is so crucial to update your sweat sheet, especially if the game goes dead. Even if the cage calls and says this player cashed out $4000 black, it won’t affect how we close out the card because we know how many checks he took off of the game.

Suppose this player was rat-holing his checks and there were other players on the game. How do we know how much he left with? Well, if the other player on the game was keeping his checks on the layout, we can mentally add his checks to the rack to compute how much our player left with. If they were both rat-holing, we might wait for the other player to leave (hopefully busted) and then we would know what the first player left with. And while we don’t like to depend on calls from the cage or the floorperson in the next section to tell us how many checks this player came to them with, sometimes we have to. And when all else fails, divide the checks you are missing between the players that left.

Sometimes as a courtesy to the next floorperson that gets this player, you can indicate what the player left with in the comments section of the card. In this case you would write;"W/W .6 b & .2 g." The "W/W" meaning "walked with." Another thing the next floorman might want to write in his comments section would be that player’s $2000 "PBI" or previous buy-ins. This gives anyone that takes over that section the heads up that if this player would to buy-in $1001 or more, he would have to be put on the MTL. In the case of PBI it is necessary to differentiate between buy-in or money plays. Another entry you mind find in the comments section of a rating card is "toke box." If the dealers dropped a significant amount of checks in the toke box, it will be counted as part of the player’s "out" and the amount under the "toke box" entry will tell your relief why the amount the player cashed out is less than what is missing from the rack.

Checks in and checks out.

This is one area that can greatly differ between casinos. Lets say a player comes to a game with 2.0 in black and left with 1.0 in black. This can be recorded one of three ways:

1.) The player is in 2,000 and out 1,000. This was the way it was done back in the Stone Age and ironically enough, the way this play is recorded in some of the new player tracking computerized systems.

2.) Player is in 1,000 and out 0. This is the way most modern casinos record this play. The most fundamental rule to follow is: "A player can only be in checks if he loses them."

3.) The way I was taught is the player would be in 0 and loses 1,000. This enables the pit manager to consolidate this patron’s play most efficiently on the "hit sheet." The pit boss would be able to add all the "ins" to know how much a player had bought in and add all the player’s win/loses to know how he did.

For the rest of this chapter we will assume that our casino uses method #2 for tracking checks in and checks out. So see how you do in the following examples:

Example 1.

The sweat sheet says 4.0 black and 2.0 green when a player lands on the game with 1.0 green. He leaves and now the rack is 3.2 black and 3.0 green. What is his total in and out?

Actually we don’t care if the player came up with 1.0 green or not. Our sweat sheet tells us we lost .8 black and picked up 1.0 green. The player is in 200 and out 0.

Example 2.

The sweat sheet say 5.5 black and 3.2 green when a player walks up with a stack of black. The player loses his black and buys-in for $2,000 cash. When he leaves the rack is at 6.2 black and 3.0 green. What is his total in and out?

The net gain of the rack is .5 from gaining .7 black and losing .2 green. The player is in 2,500 and out 0.

Example 3.

The sweat sheet say 5.5 black and 3.2 green when a player walks up with a stack of black. The player loses his black and buys-in for $2,000 cash. When he leaves the rack is at 5.0 black and 3.3 green. What is his total in and out?

The net loss of checks in the rack is .4, from losing .5 black and picking up .1 green. So this is not really a "checks in, checks out" situation at all. The player is in 2,000 (cash) and out 400.

Example 4.

A player comes with 1.0 black and when he leaves you are missing .5 black.

The player is in 0 and out 500.

Example 5

A player comes with 1.0 black and when he leaves your rack is the same.

The player is in 0 and out 0. Unless this player was a "R/N" you would still turn in a card so he gets credit for his play.

Indicating markers as total in.

A player can only be in markers as total in if he fails to pay them back that play. If he were to pay them back it would be as though they never happened. If he pays back a marker that was gotten on a previous play, then it would be considered part of his total out.

Transferring rating cards and other tricks.

Some floorpersons have an aversion to writing more rating cards than they have to and some pit bosses dislike dealing with more rating cards than they have to. Sometimes an opportunity to transfer a card from one game to another or even from one section or pit to another will present itself.

Suppose a player buys-in for $2,000 cash and leaves with 1.0 black. I now see he is heading to another game in the next section. I give the rating card to the floorperson and tell him that this player is in $2,000 cash and has exactly 1.0 in black. This floorperson will now add 1.0 black to the sweat sheet of the table the player lands on. So as far as this floorperson is concerned, this player is in $2,000 cash, period. And when the player leaves he can close out his rating card based on the condition of the rack compared to the sweat sheet.

If the player came to my game with checks and lost some of them, then the floorperson I want to transfer the card to would subtract checks from his sweat sheet. The easy way to remember this technique is that the next floorperson is going to do the opposite to his sweat sheet than the previous floorperson did to his.

Another tactic is for when a player lands on your game with checks, loses them and then buys-in for cash. If this player were alone at the table, it would not be difficult to track his play. But if there are other players on the game, especially ones that came up with checks, I might decide to close out the rating card for the player losing his checks, add the checks to the sweat sheet and then start a new card for the cash buy-in.

Rolling the shift.

There is nothing quite like the shift change to test the powers of your multi-tasking abilities. As the floorperson you are responsible for making the new sweat sheet or table cards for the new shift as well as closing out the rating cards for old shift and starting new rating cards based on the checks your players have at the count.

At this time of the day, you can’t count on anyone or anything making your job easier. The incoming and outgoing shift bosses try to break the land speed record so the outgoing shift boss can go home or just for the sheer joy of watching you struggle. Add to this the fact that the players that have been sitting there for five hours will choose this moment to ask you for comps and the dealers will be screwing up two games ahead of the count team.

There is one of two ways we can record the amount of checks the players have at the count. We can make out new rating cards about a half an hour before the shift change. We close out the old cards as far as time, leaving only the total in and out blank. We write new cards for the new shift, including the start time (one minute after the time we choose to close out the old cards). Then as they count the game you look at the checks in front of the player, including their next bet and write them in the comments section of the old rating card. The second method is to write the amount of checks the players have on a piece of scrap paper.

Then after the count team has zipped by, you compare the total of the checks you wrote for all the players on a game and compare it to how many checks you are missing from the rack (based on the difference between the closing amounts of the old sweat sheet and the opening amounts on the new sweat sheet). If they are close then that is what you go with. You close out the old rating cards based on those amounts and open the new cards for the same amounts.

If there are serious discrepancies, then you need to decide which player or players you are going to give those checks to. You might have an idea of which player has gone south with the checks or you might not. In the case of "not" you will have to adjust the amounts that you close out and open new cards based on your best guess. The only thing that is truly important is that your old rating cards reflect the total amount of checks that have left the rack.

The art and science of computing a player’s average bet.

As you will learn in a future chapter, a player’s ability to get comps is based on his rating. His rating is based on his average bet and the amount of time he plays. Fortunately, I have never worked in a place that criticized me for the average bet I gave a player. If I thought he deserved a $30 average, then I gave him a $40 average, just so he couldn’t beef. Some of my co-workers took the company’s guidelines a bit too seriously.

I was a pit manager and was collecting closed out rating cards so I could update the hit sheet. I picked up a card from this one floorperson that had a player in $1000 and out 0. The player played for ten minutes and the floorperson gave this player a $10 average! I walked back and handed the floorperson the rating slip and said; "Is this even possible? How can you give this player a ten dollar average bet?" She replied; "Well the shift boss told me to base the average bet on just the first two bets."

"The first two bets" philosophy is probably based on the belief that a player should not be rated based on bets that he makes with "the house’s money." Advocates of this belief feel that if a ten-dollar bettor gets lucky and presses his bets up to one hundred dollars, he shouldn’t be rated as a one hundred dollar player. That is why floorpersons are sometimes required to record the first two bets on the rating card, so the pit manager can insure that the final average bet isn’t significantly larger than the first two bets.

In craps, you might find something like this in the comment box of a rating slip: 25D/2x25D/60/20. The floorperson is indicating that this player generally makes a $25 pass line bet with double odds, two come bets with double odds, a total of $60 in place bets and a total of $20 in prop bets. Which leads me to another point: rating is based on the expected win from a player and expected win is based on the house percentage of the bets the player makes. Since the house has no advantage on odds taken or laid on pass line, don’t pass, come or don’t come bets: a player shouldn’t get credit for the odds he takes or lays. However, so many players have bitched about this over the years, most casinos instruct floorpersons to give a player credit for a portion of the odds he takes when computing average bets.

2.) NAME: it has to be legible and spelled correctly. If the player doesn’t want to give his name, then use "R/N" (refused name) and a very brief description so your team can tell this player from the dozens of other R/N’s. Good examples are "black hat" or "gray polo."

3.) PLAYER ID# or DOB (date of birth): it easier to look up a player in the computer using their account number. DOB can be useful if the player has a common name and you don’t know his account number. It is also useful if the player has a credit line and you don’t know his credit line account number yet.

4.) DATE: remember, if it is 1:00 am but the shift hasn’t rolled, it will be yesterday’s date.

5.) TIME IN / TIME OUT: pretty cut and dry here. Time can be written using the conventional method (without am or pm) or using military time. You want to avoid using a time-out time that is later than the time-in time that another floorperson has started this player’s next card, as this will cause overlapping play times.

6.) GAME & TABLE #: BJ 9, CR 4, RO 2 etc.

7.) SEAT: this is very important and easy to write in what playing spot a player is using on a BJ game or what position he is on a crap game. If this space isn’t offered on the rating card, I will write it in the upper right-hand corner of the card.

8.) SKILL: I have never worked in a place that uses this spot but some places use a player’s skill (or lack thereof) in determining their rating. A player that uses good basic strategy in BJ or only bets the pass line with full odds, will get a lower rating than someone who splits fives or only bets the hardways.

9.) CREDIT LINE: this is the total amount of this player’s credit line before he took any markers. Notice the form differentiates between credit extended to a player and front money the player has deposited in the cage. The reason being, a shift boss won’t be likely to raise the credit limit of someone that can only get markers because he deposited money at the cage.

10.) CREDIT REQUESTED: this is where you write in the markers this player has taken.

11.) BUY-INS: form "A" is much better designed to accommodate the necessity of indicating a chip purchase and a "losing money plays" separately. This is necessary for CTR reporting requirements. You will enter amounts using the "|’s" "V's" and "X’s" just like on your sweet sheet or table card.

12.) TOTAL IN: this will be the total amount of buy-ins, unpaid markers and lost checks. Numbers entered in total in, total out and win/lose will be written out in the conventional method, with two thousand being 2000, not 2.0

13.) TOTAL OUT: this will be the amount of the checks the player left with.

14.) WIN / LOSE: how much the player won or how much the player lost.

15.) AVERAGE BET: the average amount of money that player had in action at any one time.

16.) NAME & ID# (In): the floorperson that started the rating card.

17.) NAME & ID# (Out): the floorperson that closed out the rating card.

Cash buy-ins and checks out.

This is the simplest play to track. If a player has bought in $2000 and leaves with $800, then his total in is $2000 and his total out is $800. This will be the case even if his cash-in was a combination of buy-ins and money plays.

How do we know that he left with $800? The answer is almost always the sweat sheet; in fact it is always the sweat sheet if this was the only player on the game. If you had 4.0 black and 2.2 green when this player landed and had 3.4 black and 2.0 green when the player left, then we know you are missing $800 in checks. This is why it is so crucial to update your sweat sheet, especially if the game goes dead. Even if the cage calls and says this player cashed out $4000 black, it won’t affect how we close out the card because we know how many checks he took off of the game.

Suppose this player was rat-holing his checks and there were other players on the game. How do we know how much he left with? Well, if the other player on the game was keeping his checks on the layout, we can mentally add his checks to the rack to compute how much our player left with. If they were both rat-holing, we might wait for the other player to leave (hopefully busted) and then we would know what the first player left with. And while we don’t like to depend on calls from the cage or the floorperson in the next section to tell us how many checks this player came to them with, sometimes we have to. And when all else fails, divide the checks you are missing between the players that left.

Sometimes as a courtesy to the next floorperson that gets this player, you can indicate what the player left with in the comments section of the card. In this case you would write;"W/W .6 b & .2 g." The "W/W" meaning "walked with." Another thing the next floorman might want to write in his comments section would be that player’s $2000 "PBI" or previous buy-ins. This gives anyone that takes over that section the heads up that if this player would to buy-in $1001 or more, he would have to be put on the MTL. In the case of PBI it is necessary to differentiate between buy-in or money plays. Another entry you mind find in the comments section of a rating card is "toke box." If the dealers dropped a significant amount of checks in the toke box, it will be counted as part of the player’s "out" and the amount under the "toke box" entry will tell your relief why the amount the player cashed out is less than what is missing from the rack.

Checks in and checks out.

This is one area that can greatly differ between casinos. Lets say a player comes to a game with 2.0 in black and left with 1.0 in black. This can be recorded one of three ways:

1.) The player is in 2,000 and out 1,000. This was the way it was done back in the Stone Age and ironically enough, the way this play is recorded in some of the new player tracking computerized systems.

2.) Player is in 1,000 and out 0. This is the way most modern casinos record this play. The most fundamental rule to follow is: "A player can only be in checks if he loses them."

3.) The way I was taught is the player would be in 0 and loses 1,000. This enables the pit manager to consolidate this patron’s play most efficiently on the "hit sheet." The pit boss would be able to add all the "ins" to know how much a player had bought in and add all the player’s win/loses to know how he did.

For the rest of this chapter we will assume that our casino uses method #2 for tracking checks in and checks out. So see how you do in the following examples:

Example 1.

The sweat sheet says 4.0 black and 2.0 green when a player lands on the game with 1.0 green. He leaves and now the rack is 3.2 black and 3.0 green. What is his total in and out?

Actually we don’t care if the player came up with 1.0 green or not. Our sweat sheet tells us we lost .8 black and picked up 1.0 green. The player is in 200 and out 0.

Example 2.

The sweat sheet say 5.5 black and 3.2 green when a player walks up with a stack of black. The player loses his black and buys-in for $2,000 cash. When he leaves the rack is at 6.2 black and 3.0 green. What is his total in and out?

The net gain of the rack is .5 from gaining .7 black and losing .2 green. The player is in 2,500 and out 0.

Example 3.

The sweat sheet say 5.5 black and 3.2 green when a player walks up with a stack of black. The player loses his black and buys-in for $2,000 cash. When he leaves the rack is at 5.0 black and 3.3 green. What is his total in and out?

The net loss of checks in the rack is .4, from losing .5 black and picking up .1 green. So this is not really a "checks in, checks out" situation at all. The player is in 2,000 (cash) and out 400.

Example 4.

A player comes with 1.0 black and when he leaves you are missing .5 black.

The player is in 0 and out 500.

Example 5

A player comes with 1.0 black and when he leaves your rack is the same.

The player is in 0 and out 0. Unless this player was a "R/N" you would still turn in a card so he gets credit for his play.

Indicating markers as total in.

A player can only be in markers as total in if he fails to pay them back that play. If he were to pay them back it would be as though they never happened. If he pays back a marker that was gotten on a previous play, then it would be considered part of his total out.

Transferring rating cards and other tricks.

Some floorpersons have an aversion to writing more rating cards than they have to and some pit bosses dislike dealing with more rating cards than they have to. Sometimes an opportunity to transfer a card from one game to another or even from one section or pit to another will present itself.

Suppose a player buys-in for $2,000 cash and leaves with 1.0 black. I now see he is heading to another game in the next section. I give the rating card to the floorperson and tell him that this player is in $2,000 cash and has exactly 1.0 in black. This floorperson will now add 1.0 black to the sweat sheet of the table the player lands on. So as far as this floorperson is concerned, this player is in $2,000 cash, period. And when the player leaves he can close out his rating card based on the condition of the rack compared to the sweat sheet.

If the player came to my game with checks and lost some of them, then the floorperson I want to transfer the card to would subtract checks from his sweat sheet. The easy way to remember this technique is that the next floorperson is going to do the opposite to his sweat sheet than the previous floorperson did to his.

Another tactic is for when a player lands on your game with checks, loses them and then buys-in for cash. If this player were alone at the table, it would not be difficult to track his play. But if there are other players on the game, especially ones that came up with checks, I might decide to close out the rating card for the player losing his checks, add the checks to the sweat sheet and then start a new card for the cash buy-in.

Rolling the shift.

There is nothing quite like the shift change to test the powers of your multi-tasking abilities. As the floorperson you are responsible for making the new sweat sheet or table cards for the new shift as well as closing out the rating cards for old shift and starting new rating cards based on the checks your players have at the count.

At this time of the day, you can’t count on anyone or anything making your job easier. The incoming and outgoing shift bosses try to break the land speed record so the outgoing shift boss can go home or just for the sheer joy of watching you struggle. Add to this the fact that the players that have been sitting there for five hours will choose this moment to ask you for comps and the dealers will be screwing up two games ahead of the count team.

There is one of two ways we can record the amount of checks the players have at the count. We can make out new rating cards about a half an hour before the shift change. We close out the old cards as far as time, leaving only the total in and out blank. We write new cards for the new shift, including the start time (one minute after the time we choose to close out the old cards). Then as they count the game you look at the checks in front of the player, including their next bet and write them in the comments section of the old rating card. The second method is to write the amount of checks the players have on a piece of scrap paper.

Then after the count team has zipped by, you compare the total of the checks you wrote for all the players on a game and compare it to how many checks you are missing from the rack (based on the difference between the closing amounts of the old sweat sheet and the opening amounts on the new sweat sheet). If they are close then that is what you go with. You close out the old rating cards based on those amounts and open the new cards for the same amounts.

If there are serious discrepancies, then you need to decide which player or players you are going to give those checks to. You might have an idea of which player has gone south with the checks or you might not. In the case of "not" you will have to adjust the amounts that you close out and open new cards based on your best guess. The only thing that is truly important is that your old rating cards reflect the total amount of checks that have left the rack.

The art and science of computing a player’s average bet.

As you will learn in a future chapter, a player’s ability to get comps is based on his rating. His rating is based on his average bet and the amount of time he plays. Fortunately, I have never worked in a place that criticized me for the average bet I gave a player. If I thought he deserved a $30 average, then I gave him a $40 average, just so he couldn’t beef. Some of my co-workers took the company’s guidelines a bit too seriously.

I was a pit manager and was collecting closed out rating cards so I could update the hit sheet. I picked up a card from this one floorperson that had a player in $1000 and out 0. The player played for ten minutes and the floorperson gave this player a $10 average! I walked back and handed the floorperson the rating slip and said; "Is this even possible? How can you give this player a ten dollar average bet?" She replied; "Well the shift boss told me to base the average bet on just the first two bets."

"The first two bets" philosophy is probably based on the belief that a player should not be rated based on bets that he makes with "the house’s money." Advocates of this belief feel that if a ten-dollar bettor gets lucky and presses his bets up to one hundred dollars, he shouldn’t be rated as a one hundred dollar player. That is why floorpersons are sometimes required to record the first two bets on the rating card, so the pit manager can insure that the final average bet isn’t significantly larger than the first two bets.

In craps, you might find something like this in the comment box of a rating slip: 25D/2x25D/60/20. The floorperson is indicating that this player generally makes a $25 pass line bet with double odds, two come bets with double odds, a total of $60 in place bets and a total of $20 in prop bets. Which leads me to another point: rating is based on the expected win from a player and expected win is based on the house percentage of the bets the player makes. Since the house has no advantage on odds taken or laid on pass line, don’t pass, come or don’t come bets: a player shouldn’t get credit for the odds he takes or lays. However, so many players have bitched about this over the years, most casinos instruct floorpersons to give a player credit for a portion of the odds he takes when computing average bets.

Site created and designed by

Scott Cameron

Las Vegas, Nevada

Scott Cameron

Las Vegas, Nevada

Email me [email protected]

Copyright 2020-2024

Last update 3/18/2024

Last update 3/18/2024

Visit my other website...